This article, which appears only here, is part of the research that gives ballast to The Immigrant Chronicles.

How German-Americans Immigrated and then Disappeared

In 1836, for the first time in history, the brute strength of human muscle, beasts of burden, and natural forces necessary to propel a craft at painstakingly slow speed was beginning to be replaced by steam power.

On a steamboat, people could now travel in comparative luxury. They could travel great distances at speeds once thought impossible -sometimes in excess of eight miles per hour!

And travel they did. Just over 22,000 non-native inhabitants were counted in areas that are now Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota in 1836 when the original Wisconsin Territory was formed. The majority of these were squatters in the lead-mining region where the three states' boundaries now meet, but this small contingent was about to be dwarfed by the millions to come, about half of them from Germany and many from Ireland. Every other European country was soon represented. By 1850 that number had grown to approximately a half million. And in the next twenty years it exceeded two and a half million people. Minnesota acquired a greater population in twenty years than had New York State in a century and a half.

The story of German migration has parallels in migrations all across the world, especially those of the mostly 19th Century Irish and Italian migrations to America, where pull and push factors combine to make people give up more than we imagine, risk more than we remember and work harder than we -- or they -- thought possible. Making a new country is not easy!

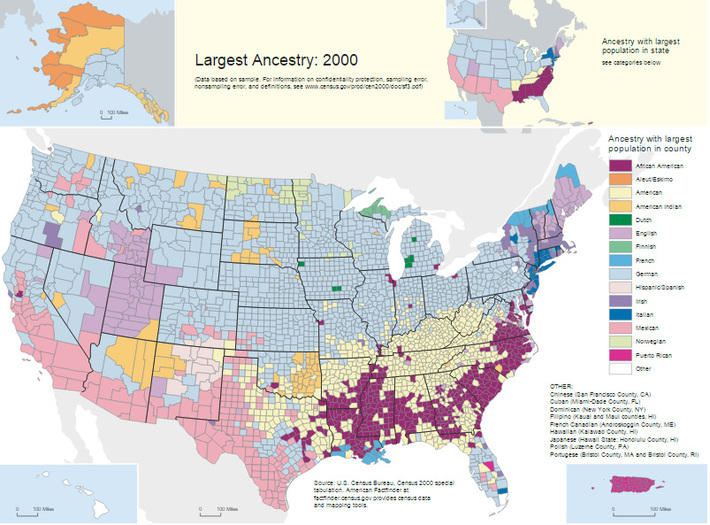

Today, Americans with German ancestry fill more towns, counties and states than Americans of any other ancestry. Those areas are marked in light blue, and more information is available at Wikipedia, "Race and Ethnicity in the United States," where this chart is interactive.

The long description below of Germans who settled Texas about the time that The 1836 Series takes place applies to much of the German immigration filling the upper Midwest,

“[Germans] were diverse in many ways. They included peasant farmers and intellectuals; Protestants, Catholics, Jews, and atheists; Prussians, Saxons, Hessians, and Alsatians; abolitionists and slave owners; farmers and townsfolk; frugal, honest folk and ax murderers. They differed in dialect, customs, and physical features. A majority had been farmers in Germany, and most came seeking economic opportunities. A few dissident intellectuals fleeing the 1848 revolutions sought political freedom, but few, save perhaps the Wends, came for religious freedom….

"Even in the confined area of the Hill Country, each valley offered a different kind of German. The Llano valley had stern, teetotaling German Methodists, who renounced dancing and fraternal organizations; the Pedernales valley had fun-loving, hardworking Lutherans and Catholics who enjoyed drinking and dancing; and the Guadalupe valley had atheist Germans descended from intellectual political refugees.

"The scattered German ethnic islands were also diverse. These small enclaves included Lindsay in Cooke County, largely Westphalian Catholic; Waka in Ochiltree County, Midwestern Mennonite; Hurnville in Clay County, Russian German Baptist; and Lockett in Wilbarger County, Wendish Lutheran….

"Many German settlements had distinctive architecture, foods, customs, religion, language, politics, and economy. In the Hill Country the settlers built half-timbered and stone houses, miles of rock fences, and grand Gothic churches with jagged towers reaching skyward. They spoke a distinctive German patois in the streets and stores, ate spiced sausage and sauerkraut in cafes, and drank such Texas German beers as Pearl and Shiner.... They polkaed in countless dance halls, watched rifle competition at rural Schützenfeste, and witnessed the ancient Germanic custom of Easter Fires at Fredericksburg. Neat, prosperous farms and ranches occupied the countryside.”[i]

Today, signs of German culture have almost entirely disappeared in America, and this is not just a matter of fading over time. Anti-immigrant sentiment flared in the 1850s with the rise of secret Know-Nothing societies. It was rife before World War I and flamed up again during World War II. After the war, when the concentration camps were opened and people around the world began to grasp the horrors of Nazism, German-Americans were revolted and ashamed. For German culture in America, the twentieth century was a time of severe setbacks--and a devastating blow from which it has never recovered.

When the U.S. declared war on Germany in 1917, virulent anti-German sentiment rose across the nation, and German-American institutions came under attack.[ii] Some discrimination was hateful, but cosmetic: the names of organizations, schools, foods, streets, and towns were often changed; people anglicized their names; and music written by Wagner and Mendelssohn was removed from concert programs and even weddings. Physical attacks, though rare, were violent: German-American businesses and homes were vandalized, and Americans accused of being "pro-German" were tarred and feathered, and, in at least one instance, lynched. More than 4,000 German-Americans were sent to prison camps in 1917-18.

The most pervasive damage was done, however, to German language and education. German-language newspapers were either run out of business or chose to close their doors. German-language books were burned, and Americans who spoke German were threatened with violence or boycotts. German Shepherd dogs were officially renamed "Alsatians," a designation reversed by the English Kennel Club only in 1977. German-language classes, until then a common part of the public-school curriculum, were discontinued and, in many areas, outlawed.

None of these institutions ever fully recovered, and the centuries-old tradition of German language and literature in the United States was pushed to the margins of national life, and in most places, effectively ended.

At the same time, thousands of German-Americans fought to defend America in World War I, led by German-American John J. Pershing, whose family had long before changed their name from Pfoerschin. Anti-German feelings arose again during World War II, and the United States government interned nearly 11,000 German-American citizens between 1940 and 1948. An unknown number of "voluntary internees" joined their spouses or parents in the camps and were not permitted to leave. When Hitler's Nazi party came to power in 1933, it triggered a significant exodus of artists, scholars and scientists, as Germans and other Europeans fled the coming storm. Most eminent among this group was a pacifist Jewish scientist named Albert Einstein. When the Nazis were defeated, it was Dwight Eisenhower, a descendant of Pennsylvania Dutch Germans, who commanded U.S. troops in Europe. Two other German-Americans, Admiral Chester Nimitz of the United States Navy and General Carl Spaatz of the Army Air Corps, played key roles in the struggle against Nazi Germany, as did millions of ordinary German-Americans.[iii]

Leslie V. Tischauser says, “The effects of two world wars in a generation, along with the memory of Adolf Hitler, was devastating to German-American ethnic consciousness. After the second war, what with the new meaning the word ‘German’ had acquired, an ethnic consciousness appeared as something to consign to oblivion, and most German-Americans did just that …. Wounded by WWI, battered by the events of the interwar years, German-American ethnic consciousness became a casualty of WWII, one more victim, however inadvertently and ironically [of war]."

Today most German-Americans have never thought of themselves as hyphenated; they are simply Americans, and when they think about it, they are ashamed or embarrassed about any connection with Nazi Germany, even if their own fathers and uncles were in American uniforms during World War II. Many have lost all or most of their family's story of the migration, and some do not even know how their names were anglicized. Their own heritage is blurred or forgotten or even lost forever.

[i] W.T. Block, “Some Notes on Our Texas German Heritage,” texasescapes.com http://www.texasescapes.com/WTBlock/Texas-Germanic-Heritage.htm

[ii] No Pro-Germans sign, Chicago, 1917, Library of Congress

[iii] Adapted from Library of Congress teaching materials, www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/german8.html

And travel they did. Just over 22,000 non-native inhabitants were counted in areas that are now Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota in 1836 when the original Wisconsin Territory was formed. The majority of these were squatters in the lead-mining region where the three states' boundaries now meet, but this small contingent was about to be dwarfed by the millions to come, about half of them from Germany and many from Ireland. Every other European country was soon represented. By 1850 that number had grown to approximately a half million. And in the next twenty years it exceeded two and a half million people. Minnesota acquired a greater population in twenty years than had New York State in a century and a half.

The story of German migration has parallels in migrations all across the world, especially those of the mostly 19th Century Irish and Italian migrations to America, where pull and push factors combine to make people give up more than we imagine, risk more than we remember and work harder than we -- or they -- thought possible. Making a new country is not easy!

Today, Americans with German ancestry fill more towns, counties and states than Americans of any other ancestry. Those areas are marked in light blue, and more information is available at Wikipedia, "Race and Ethnicity in the United States," where this chart is interactive.

The long description below of Germans who settled Texas about the time that The 1836 Series takes place applies to much of the German immigration filling the upper Midwest,

“[Germans] were diverse in many ways. They included peasant farmers and intellectuals; Protestants, Catholics, Jews, and atheists; Prussians, Saxons, Hessians, and Alsatians; abolitionists and slave owners; farmers and townsfolk; frugal, honest folk and ax murderers. They differed in dialect, customs, and physical features. A majority had been farmers in Germany, and most came seeking economic opportunities. A few dissident intellectuals fleeing the 1848 revolutions sought political freedom, but few, save perhaps the Wends, came for religious freedom….

"Even in the confined area of the Hill Country, each valley offered a different kind of German. The Llano valley had stern, teetotaling German Methodists, who renounced dancing and fraternal organizations; the Pedernales valley had fun-loving, hardworking Lutherans and Catholics who enjoyed drinking and dancing; and the Guadalupe valley had atheist Germans descended from intellectual political refugees.

"The scattered German ethnic islands were also diverse. These small enclaves included Lindsay in Cooke County, largely Westphalian Catholic; Waka in Ochiltree County, Midwestern Mennonite; Hurnville in Clay County, Russian German Baptist; and Lockett in Wilbarger County, Wendish Lutheran….

"Many German settlements had distinctive architecture, foods, customs, religion, language, politics, and economy. In the Hill Country the settlers built half-timbered and stone houses, miles of rock fences, and grand Gothic churches with jagged towers reaching skyward. They spoke a distinctive German patois in the streets and stores, ate spiced sausage and sauerkraut in cafes, and drank such Texas German beers as Pearl and Shiner.... They polkaed in countless dance halls, watched rifle competition at rural Schützenfeste, and witnessed the ancient Germanic custom of Easter Fires at Fredericksburg. Neat, prosperous farms and ranches occupied the countryside.”[i]

Today, signs of German culture have almost entirely disappeared in America, and this is not just a matter of fading over time. Anti-immigrant sentiment flared in the 1850s with the rise of secret Know-Nothing societies. It was rife before World War I and flamed up again during World War II. After the war, when the concentration camps were opened and people around the world began to grasp the horrors of Nazism, German-Americans were revolted and ashamed. For German culture in America, the twentieth century was a time of severe setbacks--and a devastating blow from which it has never recovered.

When the U.S. declared war on Germany in 1917, virulent anti-German sentiment rose across the nation, and German-American institutions came under attack.[ii] Some discrimination was hateful, but cosmetic: the names of organizations, schools, foods, streets, and towns were often changed; people anglicized their names; and music written by Wagner and Mendelssohn was removed from concert programs and even weddings. Physical attacks, though rare, were violent: German-American businesses and homes were vandalized, and Americans accused of being "pro-German" were tarred and feathered, and, in at least one instance, lynched. More than 4,000 German-Americans were sent to prison camps in 1917-18.

The most pervasive damage was done, however, to German language and education. German-language newspapers were either run out of business or chose to close their doors. German-language books were burned, and Americans who spoke German were threatened with violence or boycotts. German Shepherd dogs were officially renamed "Alsatians," a designation reversed by the English Kennel Club only in 1977. German-language classes, until then a common part of the public-school curriculum, were discontinued and, in many areas, outlawed.

None of these institutions ever fully recovered, and the centuries-old tradition of German language and literature in the United States was pushed to the margins of national life, and in most places, effectively ended.

At the same time, thousands of German-Americans fought to defend America in World War I, led by German-American John J. Pershing, whose family had long before changed their name from Pfoerschin. Anti-German feelings arose again during World War II, and the United States government interned nearly 11,000 German-American citizens between 1940 and 1948. An unknown number of "voluntary internees" joined their spouses or parents in the camps and were not permitted to leave. When Hitler's Nazi party came to power in 1933, it triggered a significant exodus of artists, scholars and scientists, as Germans and other Europeans fled the coming storm. Most eminent among this group was a pacifist Jewish scientist named Albert Einstein. When the Nazis were defeated, it was Dwight Eisenhower, a descendant of Pennsylvania Dutch Germans, who commanded U.S. troops in Europe. Two other German-Americans, Admiral Chester Nimitz of the United States Navy and General Carl Spaatz of the Army Air Corps, played key roles in the struggle against Nazi Germany, as did millions of ordinary German-Americans.[iii]

Leslie V. Tischauser says, “The effects of two world wars in a generation, along with the memory of Adolf Hitler, was devastating to German-American ethnic consciousness. After the second war, what with the new meaning the word ‘German’ had acquired, an ethnic consciousness appeared as something to consign to oblivion, and most German-Americans did just that …. Wounded by WWI, battered by the events of the interwar years, German-American ethnic consciousness became a casualty of WWII, one more victim, however inadvertently and ironically [of war]."

Today most German-Americans have never thought of themselves as hyphenated; they are simply Americans, and when they think about it, they are ashamed or embarrassed about any connection with Nazi Germany, even if their own fathers and uncles were in American uniforms during World War II. Many have lost all or most of their family's story of the migration, and some do not even know how their names were anglicized. Their own heritage is blurred or forgotten or even lost forever.

[i] W.T. Block, “Some Notes on Our Texas German Heritage,” texasescapes.com http://www.texasescapes.com/WTBlock/Texas-Germanic-Heritage.htm

[ii] No Pro-Germans sign, Chicago, 1917, Library of Congress

[iii] Adapted from Library of Congress teaching materials, www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/german8.html

Website by Kleidon & Associates